On Home Affordability, Poverty, and Unlawning America

I don’t know who that Michael Green financial analyst guy is who looked at one county in NJ to state

[from 2018]

This was my second time. The first was about four years ago when our front lawn was taller than six inches and had a few dozen dandelion seed heads in it. Three months after that notice I tore out most of the yard and put in large prairie garden beds. No one has reported the space since, oddly enough.

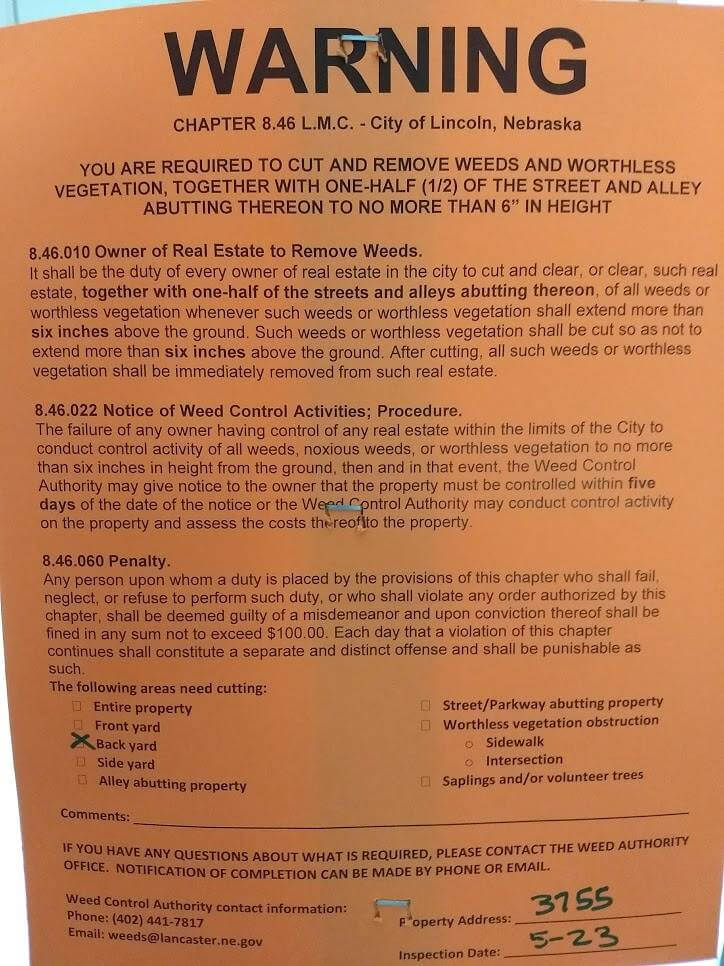

On May 23 of this year we received another warning — this time a bright orange sign staked into the middle of the front yard — notifying us we had to cut down the back meadow (just weeks before a local garden tour). This designed space began in 2015 because I refused to water a lawn we never used, that burned hard every July and August, and was becoming patchy; it’s also become a wonderful proving ground for my thriving business.

After sending a plant list to the local weed superintendent, he was gracious enough to meet at my home to discuss the issue. Here’s how it went, what we both learned, and what you need to take away as we move to more sustainable wildlife landscapes in urban areas.

—————-

At first we were both in our ideological corners. I was being quoted ordinance about vermin, snakes, and fire, while I was quoting stats about snakes eating mice, native bee decline, and the low burn temperature and quick burn time of prairie grasses. I planned to approach our talk as calmly as possible, but after pacing for a solid hour beforehand I’d worked myself up. So, the first lesson is don’t pace for an hour beforehand.

But after awhile we settled into a very productive and friendly half-hour conversation I was thankful for. We taught each other and, I believe, pledged to work together here and around town. One of the largest sticking points centered on cutting down plant material in fall so as not to be a fire hazard. Since every garden I design is planned to be aesthetically pleasing in winter — not to mention a haven for birds and overwintering insects — I kept coming back to how we needed to find a solution to have the garden standing. Heck, in spring I leave 12-18″ of stubble for nesting bees. Eventually, I heard “hey, if no one complains in winter I won’t come knocking on your door.”

As we walked around I was able to provide the Latin and common names to over 90% of the plants (I should have had coffee because I can hit 100% just fine). And as I discussed plant communities, how the space was designed, what the intention was and how it would continue to develop, the superintendent noted that it was clear I knew what I was doing. He even said both my front and back gardens could serve as an example of what and how to design effectively and avoid the hassle or stress such meetings produce. The other inspector that came along mentioned that as we face climate change, these types of lawn alternatives will have to become more prevalent — I’m sure not only for aesthetics but as a practical purpose to help combat the invasive exotics their department diligently patrol. Open ground is an invitation to real weeds.

It was a wonderful, energizing conversation and I felt like there was room for future collaboration, especially as we noted some struggling public spaces around town that had recently been planted but were filling up with weeds. The super also asked me what I tell people at my talks about designing a space all species can be comfortable with, and I’ll tell you what we agreed on and what I say everywhere I can:

1) It can help to hire a professional to get you started. That can be a landscape plan, a consult, or a coach that keeps coming back to help you progress. You can install a design yourself or have the professional do it for you then modify on your own, but having good bones is critical — especially in front yards (my backyard has a wood fence and faces acres of dense red cedars, but I still got in trouble).

2) Plant in masses and groups and tiers. These are traditional design strategies that we’re all accustomed to, and so they help folks see that a landscape has intention. Grouping plants also serves as a larger beacon for pollinators flying overhead, so design with 3, 5, or 7 of a kind. Have tall plants in the back or middle with shorter plants toward the front. Don’t just toss out a bag of seed or let the lawn go to see what comes up. Convert the space quickly or do it one piece at a time over years.

3) Always have something in bloom. People like flowers and flowers show intention — plus bloom succession is critical for pollinators.

4) Have a mowed edge around beds that abut sidewalks, driveways, or property lines. In lieu or combination with that strategy is placing low plants along the edges. For example, I have nothing that gets taller than 2 feet within 4-6 feet of the sidewalk. Hey, people don’t like to be touched by plants they don’t know.

5) Have a sign that says what you are doing and why. The super mentioned signs significantly mitigate their workload. Something as simple as “This is a low-maintenance, native plant pollinator garden.”

6) Show human use by including a sitting area, bench, or mowed pathway through the space. Using sculpture or fountains also helps create visual foils so it’s easier to interpret the space and focus on what might at first seem chaotic wildness (even if plants are grouped and tiered — anything that isn’t lawn up to the foundation walls is suspect).

7) Native plant pollinator gardens don’t have to look like meadows. They can be more simple and modern looking, or formal and angular. There is a middle way, too, a place where we can all meet in the landscape.

8) Talk to your neighbors. Tell them what you’re doing. Invite them over for drinks. Knock on doors and calmly / warmly ask if they’d like to talk about it or see it. Don’t accuse anyone of anything or act like you’re better then them. Educate. Teach. Welcome. Even if you’re a passionate activist who believes the sixth mass extinction is here and our over-manicured lawns are creating an ethical crisis that will consume us all (ahem), hold back and just listen. We can still have constructive and friendly conversations regardless of what is modeled for us online and in the news.

So there you go. Rest assured, there are ways to design a space that not only passes weed control inspection, but that can model where we need to go. Lush, layered gardens using interlinked plant communities lower air temps, clean that air, sequester carbon, reduce runoff into storm drains, provide valuable habitat, combat invasive weeds, and increase home values while making us psychologically and physically healthier.

Additionally, in my research leading up to the on-site meeting, I gathered some helpful links debunking common weed ordinance concerns (pests, fire, etc), as well as legal precedents from around the country if your case goes to court.

As Natural Landscaping Takes Root We Must Weed Out Bad Laws (25 years old, so there is surely more legal precedent to find)

Weed Laws and Ordinances (lots of links)

Sourcebook of Natural Landscaping for Local Officials (incredible treasure trove of why, how, and where)

It’s amazing to me that we’ve been struggling with the same issue for decades now — even when “natural” garden design was once the default landscape mode long before lawns came into vogue just after mid century. But what we see is what we accept, and what we see is what we assume is good. The prevalence of highly-managed lawn, and wood mulch as a design aesthetic in its own right, is harming a push toward sustainable design — we need more public examples of what we can do, even if those examples require more intensive management to withstand scrutiny.

One final note — the super said it’s important for folks to know landscapes like mine are also high maintenance like lawn. I’m not sure. I mow the back meadow in spring and am done. The front 400 foot garden and the older 1,500 foot main garden I simply use a hedge trimmer on and leave the detritus as natural mulch (another ordinance no no, even if it’s what more and more large public gardens do). Obviously, if you try to take on more than you can chew from the outset then you can get overwhelmed, give up, and let the weeds come in. But for me, I honestly spend one day a year in spring doing the majority of my work. With tight-knit plant communities (layers of plants on 12 inch centers or closer), my big job is cataloging wildlife and observing plant growth — with the occasional yanking of a tree seedling, musk thistle, or bush honeysuckle.

I don’t know who that Michael Green financial analyst guy is who looked at one county in NJ to state

Oh that’s a cool plant, stiff goldenrod, Oligoneuron rigidum. I wonder if that would work in my garden. Maybe it’s