If you’ve been perusing this website for a little while you’ve learned the basics of matrix design using plant sociability to select plants for said matrix. If you want to go super deep we offer online classes, pocket guides, booklets, and yes a really nice book entitled Prairie Up. On the flip side, this page is all about a crash course in design; over the next few images we’re going to show you how we’d create a 64 square foot garden — and how you can use that small design to create an infinitely scalable natural landscape with wild intention.

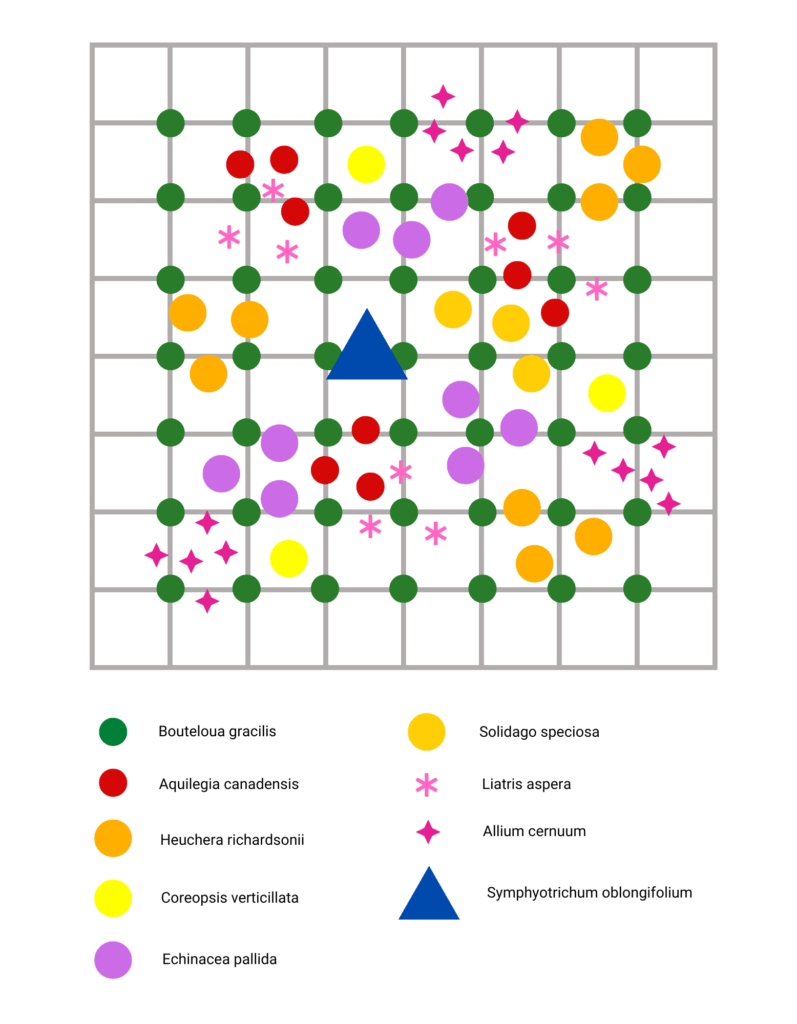

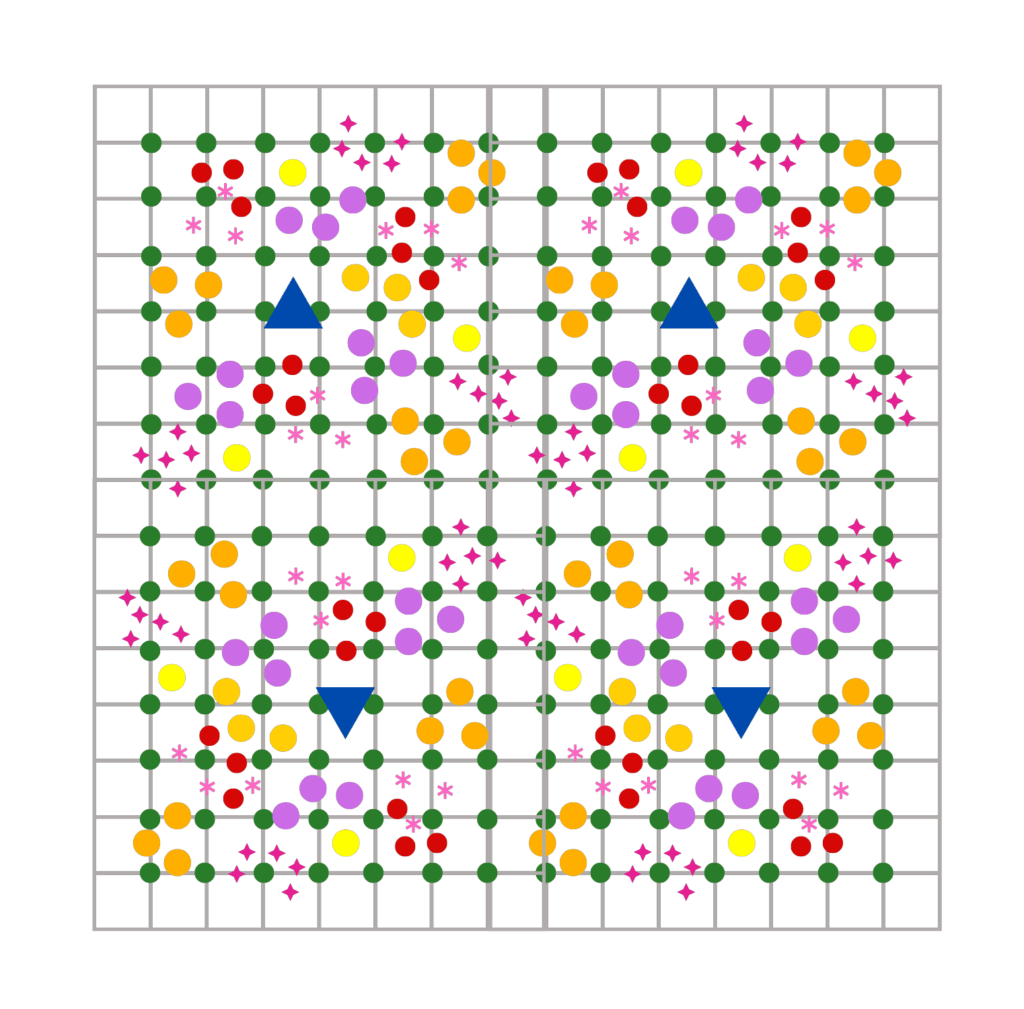

So if you look to the right (desktop / tablet) or below (phone), you’ll see our master plan that might at first look a little overwhelming and quite busy. Let’s go through it step by step so you can see how the pros approach natural design.

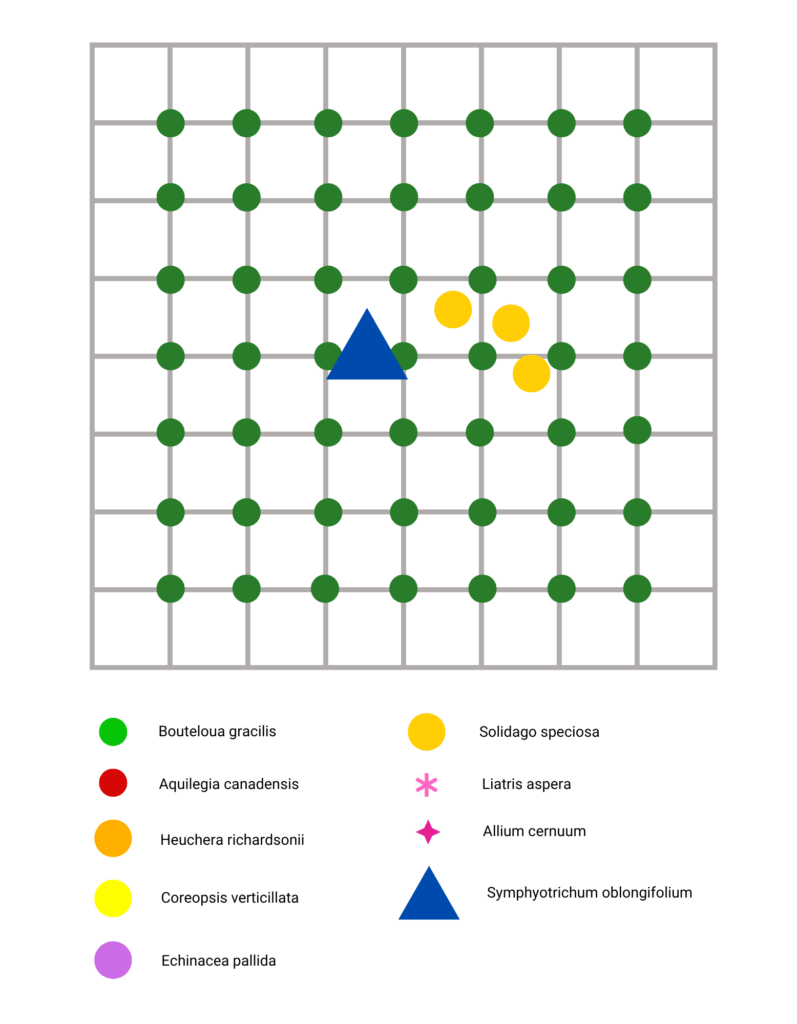

First, these plants have been chosen for a full sun site on clay to clay-loam soil with medium to dry conditions — so think decent moisture in spring and fall but dries out in summer. The bed may be on a flat grade or a slope of almost any degree. These plants are also native to the eastern Plains and Midwest mostly, but several have ranges that go beyond that — you’ll need to research the plants to make sure they are native to you and will work for your site conditions (both topics we’ve covered on the FAQ and Matrix pages under the Design tab). Most of these species evolved in the same wild plant communities so we know they should perform well together. However, one of the most essential criteria for our plant palate is behavior in a clay soil, full sun, densely-layered, tightly-knit plant community; because in a small bed the last thing you want is uber-gregarious plants, so we’ve selected species with the same sociability ranking on the low end. Here is how the following plants would thus rank on our site on a 1-4 scale:

Bouteloua gracilis — 1-2

Aquilegia canadensis — 2

Heuchera richardsonii — 1

Coreopsis verticillata — 1-2

Echinacea pallida — 2

Solidago speciosa — 1-2

Liatris aspera — 1-2

Allium cernuum — 2

Symphyotrichum oblongifolium — 2

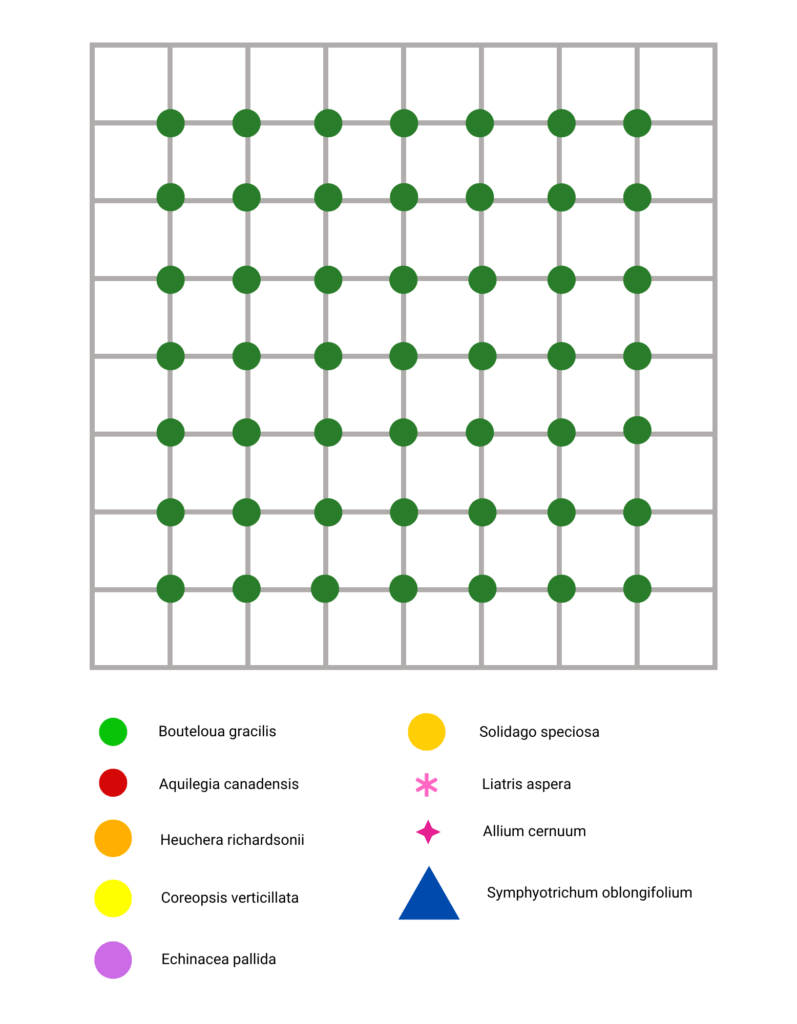

This bed was previously lawn. It was prepared using one treatment of glyphosate OR smothering, mowed short, and then a 1-2″ layer of shredded wood mulch was spread on top.

Each green dot represents one Bouteloua gracilis plug on this 12×12 inch grid pattern. Each grass should get roughly 12-18″ tall and wide — perfect to help cover the ground and provide a living green mulch layer so we never have to use wood mulch again, or worry as much about weed pressure over time.

Certainly, to spice things up, what you could do is replace a triangle of three gracilis with three Bouteloua curtipendula or three Schizachyrium scoparium. Spicy, right? Just keep in mind that a more consistent and simple and clean base layer or matrix is going to help others read the landscape and see it as less messy — in a larger bed you could do more triangle substitutions even easier.

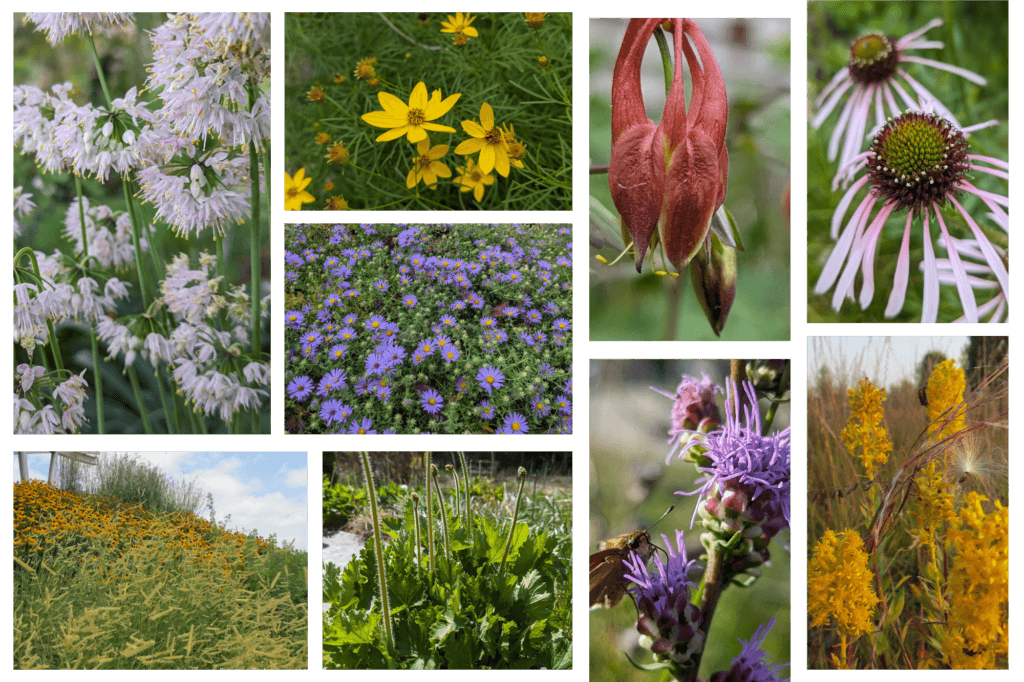

Now, you could use Bouteloua curtipendula or even Schizachyrium scoparium as the lone matrix grass. We prefer the short more open habit of B. gracilis as well as it’s very showy seed heads — plus, we’ve selected shorter forb species that will easily blend in and provide a continuity of structure and height to improve the aesthetic quality and de-wild the space a bit without losing species diversity or ecosystem function.

Now, once you gain experience with this sort of natural design, you can up the ante at the matrix level by adding more plant species. Some adaptable sedge that green up earlier in spring and help creat a thicker green mulch, like Carex blanda or Carex albicans, would do well. You could also bring in any number of shorter forbs like Anemone patens, Geum triflorum, Geranium maculatum, and Callirhoe involucrata. But for now, let’s keep it as simple and as cohesive as possible and look at the seasonal bloom succession through the seasonal layers.

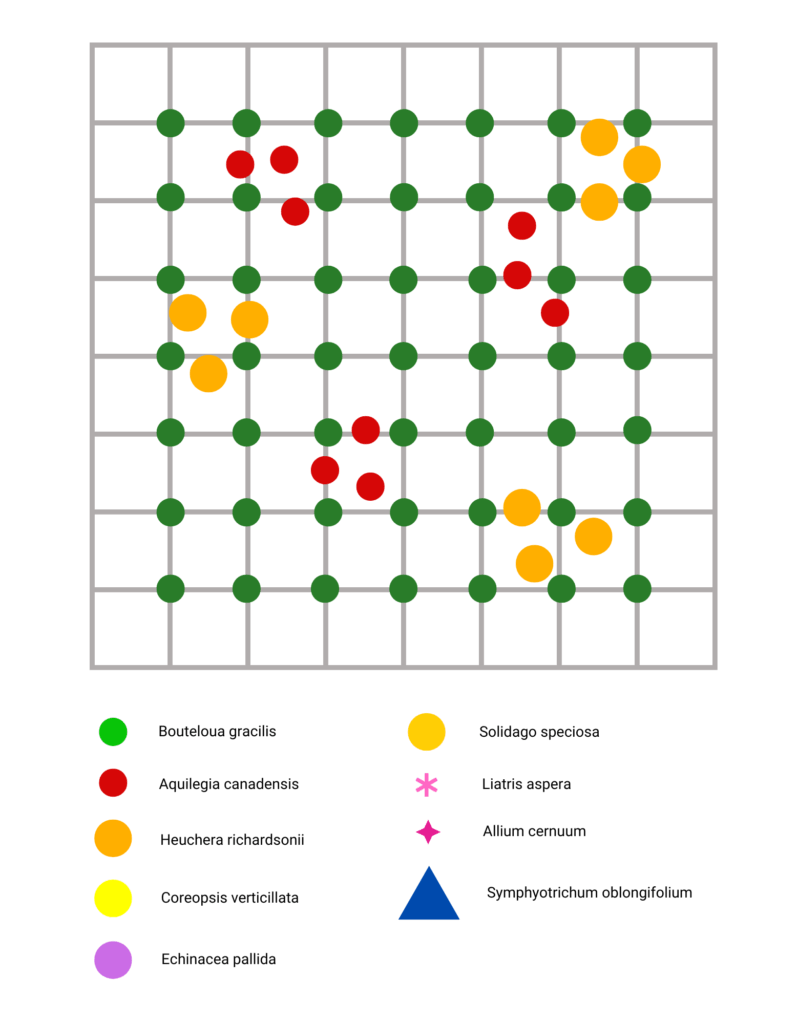

This is a very small bed and the last thing we want to do is visually overwhelm it with too many flowers and too much of a cacophony. Again, in a larger landscape we can get away with more. But never fear, we still have way, way, way more habitat and ecosystem services happening than a lawn or a “traditional” garden bed where plants are marooned from another in an ocean of mulch.

In our spring blooming period the two main plants are Aquilegia canadensis and Heuchera richardsonii. Aquilegia will self sow around a bit, which we want (or you can plant a group of 5 plants to get things going sooner), while the Heuchera provides a stellar foliage show that will contrast nicely with the finer texture of the Bouteloua matrix. Plus, that Heuchera foliage looks nice in autumn and winter, too.

Now, if over time you felt this wasn’t enough bang of the buck, one suggestion would be to increase the Heuchera groups or masses to five or seven specimens each and get them tight together. You could also bring in a beardtongue such as Penstemon cobaea or P. digitalis. Another plant group to look at would be false indigos such as Baptisia minor or Baptisia bracteata, but there’s probably enough going on for this small of a space, especially given the summer and fall forb layers that will also fill in with more stem and leaf biomass. Oh the habitat and ecosystem services that even just the foliage provides compared to a short-clipped lawn!

Not all of these species will bloom at once, which is good because we want more consistent bloom succession for both pollinators and humans coming to admire your unlawned landscape.

First up in early to mid summer will be the Coreopsis and Echinacea. Now, luckily you can sub these out if you want with similar species such as Coreopsis lanceolata or Coreopsis palmata (they are a bit more gregarious but will be solid fillers), as well as Echinacea purpurea which blooms 1-2 weeks after E. pallida.

If the bed were twice as big we’d be fans of increasing the showy summer seasonal layer via some Asclepias tuberosa and Anemone virginiana. Maybe also Dalea purpurea or Dalea candida.

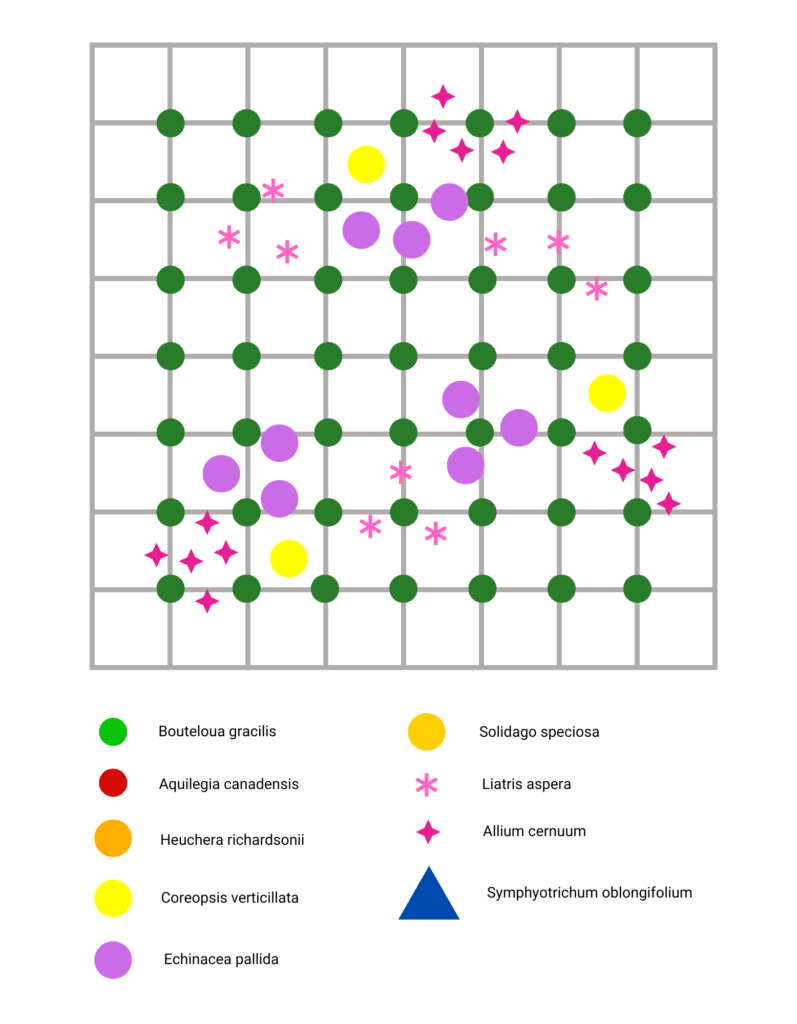

About mid to later summer the Liatris aspera and Allium cernuum come online. If you’d like to increase the Allium drifts to 7 or 9 specimens go for it — it will take them more time to produce new bulbs in a clay soil then a loamy one anyway (no one has ever complained of having too many plants).

The Liatris is a very open, sculptural, and vertical species with what we feel are very cool looking buds just before they burst into bloom. Well, let us know what you think when you grow it.

The autumn bloomers may not seem like that many, but rest assured that all of the plants that have bloomed up until now will be developing some nice seed heads, and senescence will begin occurring (aka fall foliage) for added color. Plus, the aster gets a few hundred blooms once mature so trust us, it’s got plenty of pop that migrating insects adore.

Don’t be shy with the goldenrod either, plus it’s one of the least sociable species we have — nothing like Solidago canadensis which also gets too tall and flops in garden beds and so is best suited to larger / wilder landscapes. And remember, goldenrod pollen is sticky, not airborne, so it doesn’t cause hayfever (that’s ragweed, Ambrosia spp).

We could have gone with three groups of three Solidago speciosa, but we worried we’d lose the showy seed heads of Echinacea in the process. Again, in a larger bed we’d vote for more masses of goldenrod, but you could probably pull off those three groups of three. We’re not too worried about the Liatris aspera taking a backseat in autumn, either, given its height and which isn’t too showy after its bud and bloom cycle — but IS still interesting with it’s cream bracts.

What do you do if you have more than 64 square — say, four times that amount? Repeat the module you’ve designed and replicate it across the landscape. You can even rotate the modules to mix it up. Of course, you might also want to increase the size of plant groupings (from 3 to 7 for example) and maybe connect some of those groups between modules, or let the plants figure it out over the next few years as they self select and self design. Hey, we should be letting the plants take the lead and learn from them, anyway.

If you’d like to explore modular matrix design a bit more, we suggest you dive into Planting in a Post-Wild World by Thomas Rainer and Claudia West of Phyto Studio.

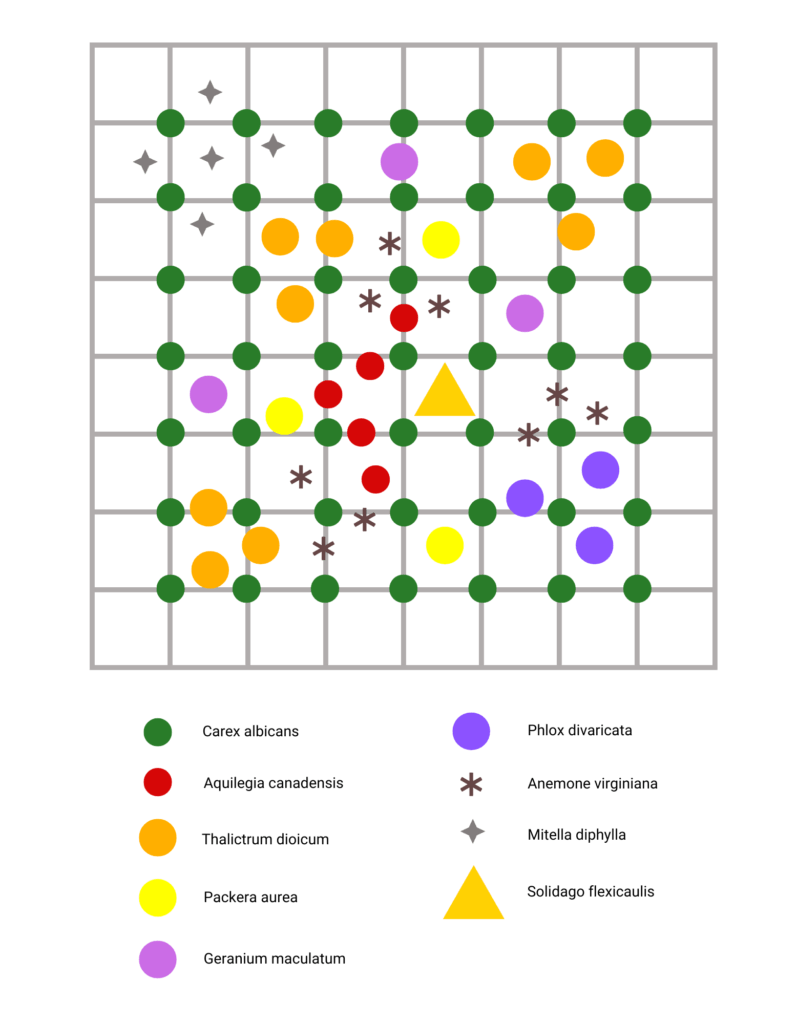

Finally, if you have a part shade or shade garden you can employ this same design method, just use the appropriate plants (eg. shade-tolerant sedge instead of sun-loving bunchgrasses) based on your site analysis and matching sociability. Same for sandy sites. Same for oh so many sites. It’s what nature does, why not us? No matter what, though, you have to do the plant research — no cookie-cutter plan can accurately know what your site conditions are like, from soil to drainage, to sunlight to site lines (this is where so many garden books fail). Even the plans provided here are simply guideposts or rough analogs — don’t take them at face value. Do the work and get empowered — it will save you time and grief in the end. We promise.

Want to see how the principles of Prairie Up were used to create a garden in Indiana?

Bouteloua gracilis x49

Aquilegia canadensis x9-15

Heuchera richardsonii x9-15

Coreopsis verticillata x3-9

Echinacea pallida x9-15

Solidago speciosa x3-9

Liatris aspera x9

Allium cernuum x15

Symphyotrichum oblongifolium x1

Estimated plant cost (plugs) = $450

Ok, we knew folks were going to ask so, real quickly, here’s a sample shade / part shade / east side garden plan for clay to clay loam in a dry to medium soil. The matrix is white-tinged sedge, Carex albicans, and we’ve used a diversity of forbs — some whose high sociability should maybe preclude them from being here, but we used them sparingly to plan for their root running (Solidago) and self sowing (Packera). We wanted to especially include the Solidago for fall color and pollinator resources. The plan is heavy on spring, which is typical in shade gardens, but ample foliage texture should help carry the summer show. As in the sun plan, we’re keeping most things on the shorter side, as well. Here are the sociability rankings for this specific site condition:

Carex albicans — 1-2

Aquilegia canadensis – 2

Thalictrum diocium — 1-2

Packera aurea — 3

Geranium maculatum – 2

Phlox divaricata — 2

Anemone virginiana — 1-2

Mitella diphylla — 1-2

Solidago flexicaulis — 2-3

FREE Lawn-to-Meadow Starter Guide

+

A Special Offer

practical tips — deep thoughts — monthly Q&A — discounts