When folks in other countries see images of sprawling expanses of lawn in American suburbs and urban areas, it’s often a shock to them. As in, they don’t have anything like that where they live. The history of lawns in the US starts with the creation of suburbs in the post civil war era, and in front yard setbacks from the street where folks grew fruits and vegetables. It wasn’t really until after World War Two, when demand for housing went into overdrive, that suburbs began to take on their current form of cookie-cutter replication, and expanses of turf that cultivated the illusion of a level socio-economic playing field, making everyone visually equal as a great democratizer, and by creating a large park-like environment all had access to.

Levittown is the poster child for the early transition. From 1947-51 over 17,000 homes replaced the native meadows of the Hempstead Plains on Long Island. Covenants in this community required weekly mowing or a crew would come mow for you then send the bill. This must certainly be where municipal weed codes and their strict implementation and reporting system came from.

Once we hit the late 1970s and early 80s, sawmills stepped in to further change what our suburban landscapes looked like. Faced with a massive excess of bits and pieces of wood from the milling process, there had to be a way to make money off of the shredded remains. That’s when we started to see mulched garden beds come along with fervor. So now we have a massive lawncare industry based on a militant regime of scheduled maintenance, herbicides, and pesticides, along with this idea that to have a healthy and successful garden bed – usually just a very thin bed pulled up tight against the house – we must use a thick layer of wood mulch reapplied every year. This high-intensity, high-input maintenance regime is great for guaranteed recurring income for landscape maintenance companies, not so great for our long-term pocketbooks or the health of these simplified ecosystems.

Making a landscape change is seldom easy, not only for reasons such as cost or lack of knowledge, but for the fact you will be creating a breach in a system that works to keep us all in line – reporting on one another when we don’t have copious amounts of lawn and wood mulch in our landscapes. But rest assured, it’s not all or nothing – especially at first.

The best place to begin your lawn conversion is where lawn already struggles: in dense shade, on steep slopes, or in areas of standing water. Other locations to think about creating a more healthy ecosystem would be in areas of your landscape you hardly use or venture into.

We have over 63,000 square miles of lawn in the continental United States (as of 2005) – roughly the size of the state of Georgia. We use 20 trillion gallons of clean water to irrigate a lawn crop we don’t eat or cultivate for clothing fiber or other durable goods. To make a comparison, we use 30 trillion gallons of water to irrigate all U.S. food crops each year.

With over 5,000 acres being converted per day – the Amazon rainforest is losing 10,000 acres per day – lawn is beyond ubiquitous while its high maintenance will soon be no longer tenable in the face of climate change. Further, of 30 commonly-used lawn pesticides, 19 are linked to cancer, 13 to birth defects, 21 to reproductive disorders, and 15 to brain damage – and that’s just among humans. Idling, not running but idling, a leaf blower for just 10 minutes produces as much toxic emissions as driving a large pickup truck for 235 miles (think F-150 or Silverado).

We live in and accept a society that inherently demands the deafening noise of lawn maintenance equipment for 12-14 hours a day each summer for 5-8 months, making conversation with one another more difficult and making the air we breathe more toxic. Lawns, seen as essential and safe play spaces, are anything but given the tools and chemicals we use to maintain the lush wall-to-wall carpeting, while in comparison kids who play in more diverse natural landscapes have reduced instances of depression, ADHD, and allergies.

How did we get here? How can we see our way out? What is the way forward when we have entire social and legal systems in place to enforce what is inherently unhealthy, yet we believe – have been sold to believe – is essential to our well being? The sweet scent of lawn being mowed, something that many of us associate with happy childhood days playing outside, is a volatile organic compound the lawn releases to warn other plants it’s under attack, to put up a defense and prepare to be eaten or damaged.

Eventually, many of us won’t be able to maintain lawns as they are now – with weekly mowing and quarterly fertilizer applications that encourage new growth, which needs more mowing, which encourages more growth, which demands more water and fertilizer. There will likely be wars over clean water. There are already massive disputes between states in the southwest and Plains over water usage of rivers for not only irrigation of farm fields but water at the tap.

The answer isn’t to mow less for one month, or to believe dandelions are the first super food flower, or to spread white clover seed, or to keep honey bees. We need less monoculture and fewer near monocultures.

Lawn is a weed that uses up valuable resources and takes over landscapes – the instant a new housing subdivision goes in the sod trucks roll through and the sprinklers turn on. And yet, we cultivate this intensive weed that, much like an invasive species, has taken over landscapes for the benefit of itself – except this weed needs a helping hand to maintain its dominance. Lawn is dependent on us to survive. We actively participate in our own loss of physical and emotional health by defaulting to all lawn, when lawn should be an area rug – a design tool in the landscape that has a purpose, like a sitting area, path, or small play space. Suburbs are not parks – if they were, we would encourage our kids to play in the streets.

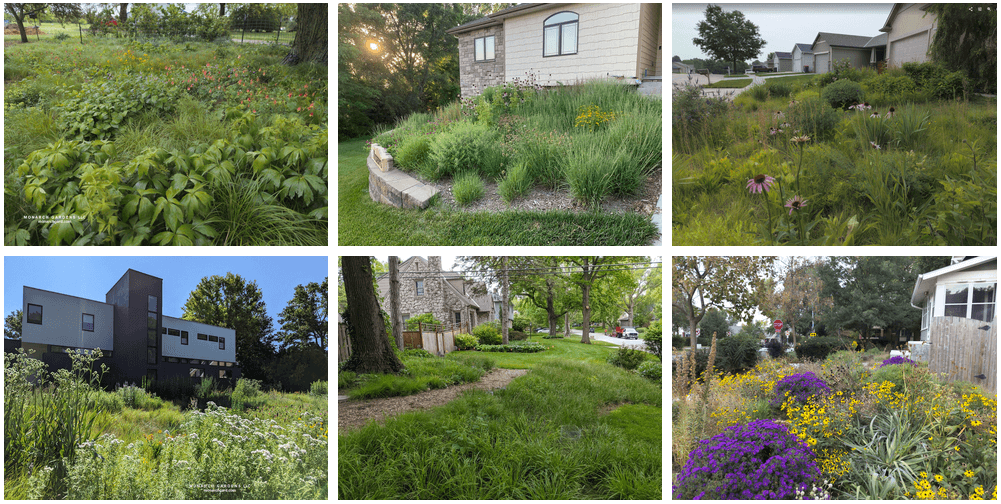

It’s easy to denigrate lawn – it’s so obvious in its drawbacks – but it also creates a space ripe for powerful transformation. It’s easy to get rid of lawn. The open space a lawn takes up is primed for an early-succession ecosystem of meadow. And even in such a meadow garden, we may use an initial, thin mulch layer, but never again. And we won’t need to use pre or post emergent herbicides if we’ve planted densely, in layers, using plants that work together to create their own living green mulch or matrix, just as we see in wilder meadows, prairies, and savannas.

It’s time to unlawn America. To rethink pretty. To see lawncare not as maintaining a monoculture but as taking it out.

FREE Lawn-to-Meadow Starter Guide

+

A Special Offer

practical tips — deep thoughts — monthly Q&A — discounts