On Home Affordability, Poverty, and Unlawning America

I don’t know who that Michael Green financial analyst guy is who looked at one county in NJ to state

If our goal is to garden for wildlife and the ecosystems they depend on, then we need to eschew hardiness zones on plant tags. But if we do that, how can we know if a plant is suitable for our landscape? We can garden by ecoregion (and as an aside, growing degree days might be worth a nod).

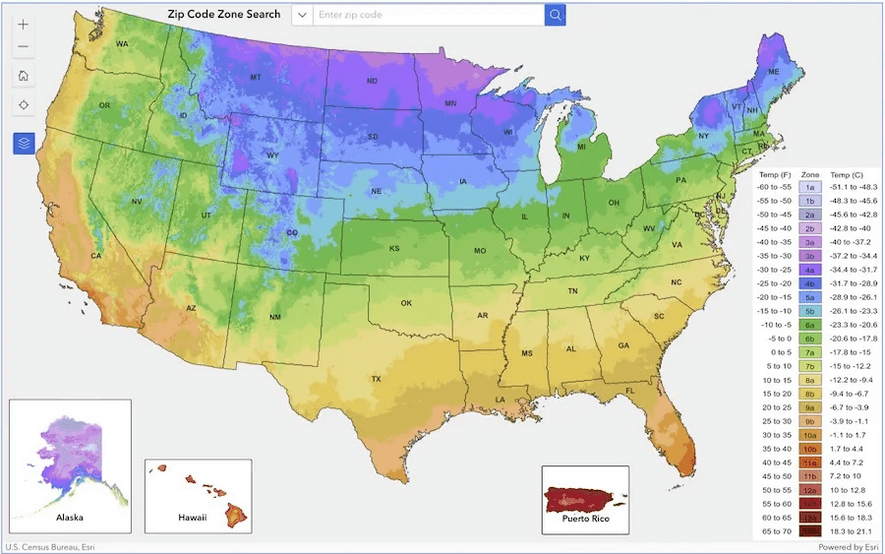

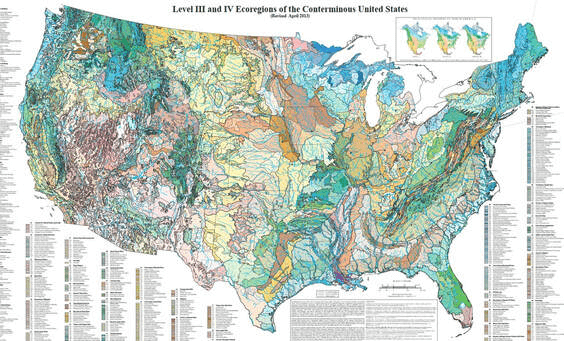

The EPA’s ecoregions focus on plant communities and regional / local climate and landsacpes, and this will mostly if not entirely mean the use of native plants adapted to your region and the wildlife that live there. Let’s compare two maps — first what we’re used to, then where we probably need to go.

Above is the map we’re all familiar with (2024 version). It’s incredibly helpful when matching plants from other parts of the world to our gardens, but as a lot of us know these plants may not be recognizable (or of use) to local fauna like pollinator adults and insect young. Another obvious issue is what’s native, even in the U.S.? A native plant from South Carolina has the same zone as a native from Oregon, but the two regions — their weather, their wildlife, their ecological communities — will be radically different for the most part. When we’re trying to garden with plants best adapted to our locale and the wildlife, we need a different map.

The EPA provides several ecoregion maps, from level 1 to level 4, the latter which is pictured above (it’s far more detailed and specific than level 1). If we look at eastern Nebraska where we’re located, there are a few ecoregions. When we try to use plants endemic from one ecoregion we’ll be more likely to have success not only in plant health and performance, but in wildlife support; this will be especially true if we can find plants grown from local ecotype seed — that’s seed gathered from within the ecoregion, sometimes even well inside that ecoregion on a hyper-local level of less than 50 miles.

You’re maybe thinking, ok great, now how do I find what’s native to me? Here’s what we suggest, which is based on the more in-depth presentation Starting Your Native Plant Garden:

1) Consult with regional plant lists created by The Xerces Society, Pollinator Partnership, and Audubon.

2) Once you have some plants you think might work on your site, further match them on the county level via a search at either BONAP or the USDA.

3) Then learn how the plants reproduce and their further cultural information. For much of the Plains and Midwest, we rely on a few sources to gather and collate horticultural details: Prairie Moon Nursery, Illinois Wildflowers, MOBOT, and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. There are many others, for sure, including regional native plant societies, nurseries, county extensions, and books, like Field Guide to Wildflowers of Nebraska and the Great Plains as well as Jewels of the Plains.

So that’s how you start, and if the journey seems complicated or long then that is ideal since you will learn so much more about your region and climate and wildlife than you ever dreamed possible — and applying that knowledge to garden design and management will be a very good thing, indeed. Prairie up.

I don’t know who that Michael Green financial analyst guy is who looked at one county in NJ to state

Oh that’s a cool plant, stiff goldenrod, Oligoneuron rigidum. I wonder if that would work in my garden. Maybe it’s