Sometimes, researching and installing plants is the simplest aspect of being different when you convert from lawn to natural garden. There may be times when you need to be an advocate for your landscape to various entities and neighbors, and those strategies can be multifaceted.

The rules of engagement have variables but also commonalities. In general, being knowledgeable (that’s why you did plant research before installing), a good listener, and calm when speaking and writing pay big dividends. And remember: you’ve made folks uncomfortable, but with a purpose in actually helping the community. Your neighbors and even city officials aren’t likely to know as much or be as passionate, or may even be constrained by legalese that is outdated but hard to change. If this sounds like you need to be both therapist and social justice agent at once, you’re correct, and it can be a tall task. But you’re up for it. Most of us just barely begin to consider rethinking our perspective after being exposed to a new idea twenty times — and only after learning to process some complex and natural emotions.

It’s critical you’re not only knowledgeable but also sound knowledgeable; this is where scientific names come into play. When you can walk around the garden and instead of using variable / imprecise common names and use Latin, you will sound like an expert. Because you are. Chances are you’ll know more than most inspectors, and certainly most neighbors or an HOA. The goal here is not to come off as smug or superior, but simply as someone who has done their research and understands what’s occurring in the garden beds. (And don’t worry about pronunciation — few do it perfectly, but we all know what you mean.)

There’s a reason your county or municipality has an invasive species weed list, and there’s a reason you shouldn’t allow any of them to grow on your property. Let HOA boards and inspectors know the breadth of your knowledge when it comes to local ordinances and ecology by saying something like “musk thistle is our biggest invasive problem and I get after it as soon as I see the basal foliage emerge.” Be proactive. Be aware. Be building bridges wherever and whenever you can.

Whether in presenting to an HOA board or doing a walk and talk with an inspector, know the ecological benefit of at least a few species (beyond milkweed) and how they are helping specific pollinator species. Point out the butterfly or moth larvae a grass or forb hosts, or the Monarda or Aster species which provides pollen to a specialist native bee. Again, this is not only about showing knowledge and expertise, but educating while building bridges because we all know about pollinator population issues by now.

Just as you should be able to identify invasive species, you should be able to identify the most common annual weeds that tend to pop up early in a new natural garden bed after soil disturbance. These weeds are not invasive or problematic even though they might look unsightly — at least for 1-2 years at most. We’re thinking crabgrass and foxtail, especially, given their height. These will fade out soon enough as desirable native plant species grow, fill in, and self sow (another reason to use only 1″ of mulch at install to allow for reproduction and free weed control via a living green mulch).

1) A plant list with scientific and common names, including images of each plant.

2) A table of bloom times, color, and anticipated mature size.

3) A table of plant sociability (eg — you won’t be using aggressives).

4) Images of inspirational gardens by landscape design firms you hope to emulate.

5) The specific wildlife benefits of each plant (milkweed for monarch egg laying):

“As you all probably know, monarch populations are down x percent in our region” or “the loss of pollinators, like bees, has been in the news, and these specific plants have been shown in this scientific study y to provide the best pollen for native bees.”

6) The specific neighborhood benefits:

7) A planting plan — even if you don’t stick with it 100% — showing placement of each and every plant no matter how tedious that will be.

8) A detailed management plan by season (when you will cut back, when you will replant, what you will be looking for as you manage, how often you will weed, etc).

9) In your design obvious areas for a table, bench, walking path, pergola, etc.

10 ) Signatures of neighbors who approve of your plan.

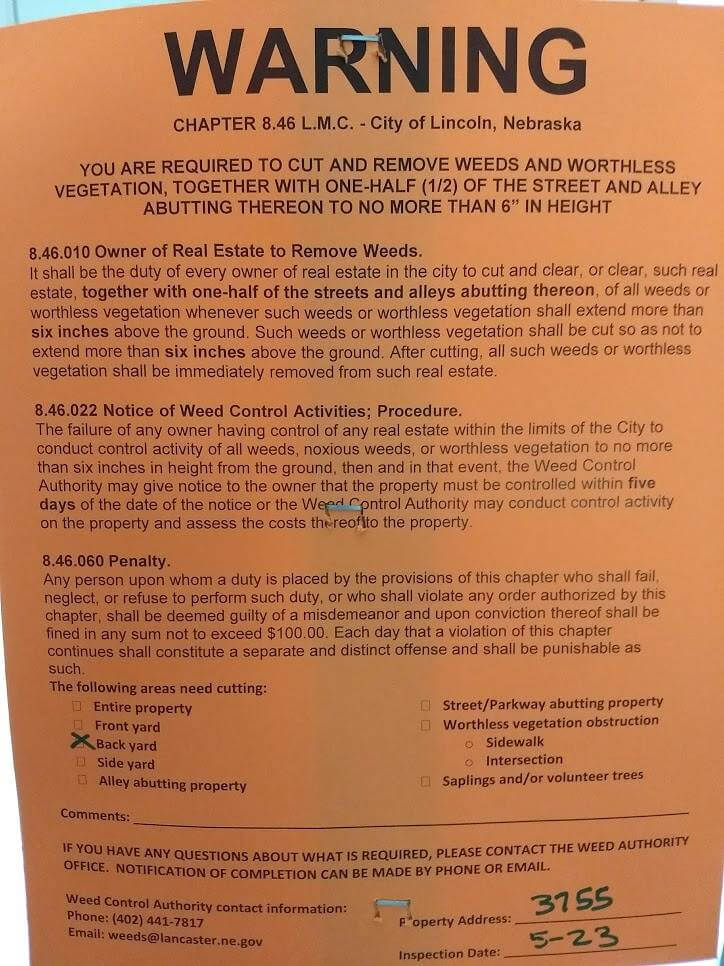

11) Awareness of local weed ordinances and prepared rebuttals for the most common points of concern: fire and pests (snakes, rodents).

12) Approval of plan by the city or county weed superintendent.

13?) Take some of our online classes to get well versed in design, management, and advocacy.

The city slapped a native plant gardener with a $600 fine but he fought back — and won.

An award-winning gardener gets busted.

Maryland couple sues HOA, wins, and changes state law.

As Natural Landscaping Takes Root We Must Weed Out the Bad Laws — how natural landscaping and Leopold’s land ethic collide with un-enlightened weed laws and what must be done about it

A professor from Toronto says city policy provides grants yet weed ordinances demand eradication.

Model Native Plant Landscape Ordinance Handbook (Florida)

Minneapolis code, section 227.90, is a progressive model for native gardens.

Stamford, CT reworks blight laws to allow frontyard meadows.

More progress from around the country on changing the landscape paradigm away from lawn.

You don’t have to fight city hall on weed laws.

Weeding Out Bad Vegetation Control Ordinances.

Green Bay updates its codes to include setback requirements and an appeal process.

Sourcebook on Natural Landscaping for Local Officials.

Chicago’s Native and Pollinator Garden Registry ensure landscapes won’t get fined.

Jersey City mandates 50-70% native plants in new municipal installations.

Colorado makes law prohibiting HOAs from banning drought-tolerant landscapes and vegetable gardens.

Illinois passes Homeowner’s Landscaping Act which allows homeowners wilder plantings in HOAs.

Evansville, Indiana revised ordinance allows 9″ of growth if plants are native and have a maintained edge.

Residents of Galveston, TX may apply for an annual “Planned Natural Landscape” exemption which allows for taller growth if utility access and borders are maintained.

Lewisville, TX (Dallas) has converted 19 acres of roadway median saving some $27k per year in mowing costs.

Pittsburgh exempts native plant gardens from height restrictions if registered with city.

In Canada? Explore some of the advocacy being done to use as a model in your community.

FREE Lawn-to-Meadow Starter Guide

+

A Special Offer

practical tips — deep thoughts — webinars — discounts