On Home Affordability, Poverty, and Unlawning America

I don’t know who that Michael Green financial analyst guy is who looked at one county in NJ to state

Don’t just dig a ten dollar hole for a one dollar plant, but also spend ten minutes researching that plant before you ever buy it. Successful, natural garden design starts at plant selection. If you end up choosing plants that will get too tall or spread too aggressively (creating a monoculture you hoped to get rid of in the first place), it’s likely that as a gardener you’ll feel more discouraged than you need to be.

While natural garden design is always about learning from the plants and letting them show you what they want, it’s also about trying our best to select species that will work well in the site conditions, in the ecoregion, and in that chosen plant community. This invariably means plants that won’t lend to the “weedy” look neighbors and weed inspectors will abhor. Of course, there are also elements of design that are critical — like placing taller plants in the middle or back of beds, repeating groupings / patterns, and have cues to care like wide paths, benches, art, signs, etc.

In this piece we’ll briefly explore several landscapes by looking at the plants, why they were chosen, and what we expect management to be.

First, it’s important to note that species discussed here may not be native to you. In fact, these plant communities may not even be applicable to your ecoregion. So as you take some of this with a grain of salt, know it’s always your job to learn your place and plant with local nature in mind.

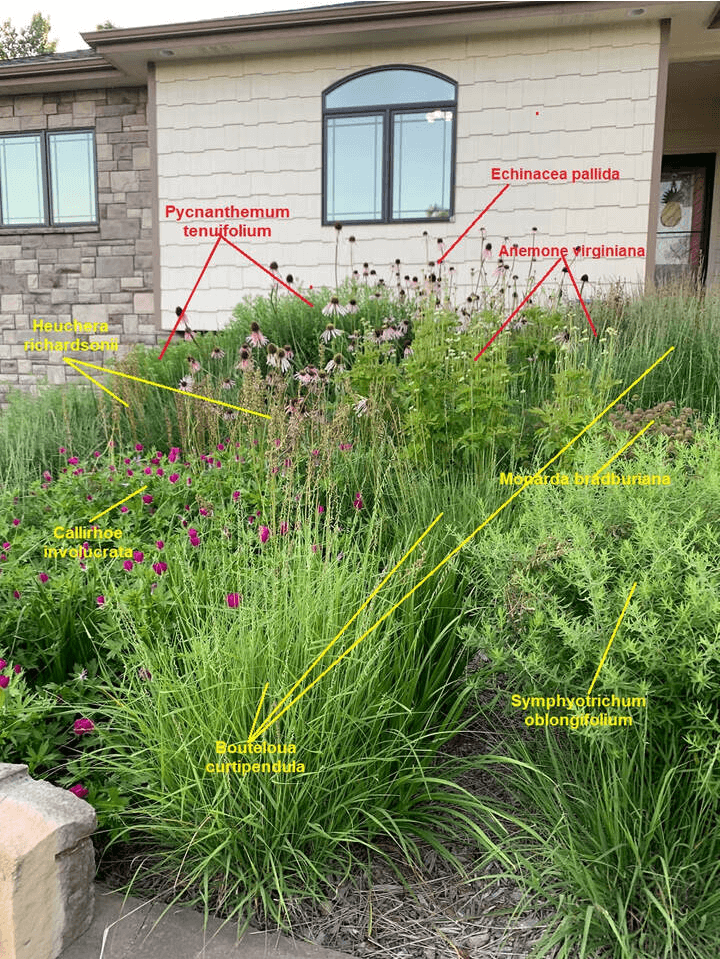

The above photo shows a roughly 350 square foot bed in front of a typical suburban home. There is a matrix of grasses — Bouteloua gracilis and Bouteloua curtipendula — planted about 15-18″ apart on center. These species become the living green mulch from which forbs emerge. All of these species can be seen growing in the wild together, and / or are from the same ecoregion and thrive in similar site conditions. This is step one to making sure your garden is off to a good start when using native species.

Second, this plant community is using each species’ natural tendencies for a purpose — to build layers and fill the ground plane, which means less weeding and erosion, and increased soil moisture and soil building. This bed was not amended. The sod was spray killed with a one-time treatment, a thin 1-2″ wood mulch layer applied, and then the plugs (younger, more affordable plants) were drilled in place.

And one more aside — notice that no plant is over 3 feet tall. This is on purpose, and part of meeting the neighborhood in the middle. There’s no floppy Ratibida pinnata or Helianthus, and no aggressively rhizomatous Asclepias syriaca (which also gets quite tall). Using those species would absolutely create a weedy look to most folks.

So let’s look at the species and what each is contributing to the community and design:

GRASSES

Bouteloua gracilis — 12-18″ green mulch / matrix / groundcover

Bouteloua curtipendula — 12-18″ green mulch / matrix / groundcover

FORBS

Callirhoe involucrata — 12″ vining groundcover weaving its way among other plants filling in gaps, long bloom season

Monarda bradburiana — 18-24″ clumping perennial that blooms in early summer and provides ornamental winter seed heads

Pycnanthemum tenuifolium — 24″ slowly rhizomatous (in clay soil) perennial that provides summer blooms and winter seed heads

Heuchera richardsonii — 12″ (24-30″ when in spring bloom) with dense basal foliage for groundcover and contrast to thinner grass leaves

Echinacea pallida — 24-36″ bloom that provides superb winter interest and structure

Coreopsis verticillata — 18″ summer bloom, slowly rhizomatous.

Anemone virginiana — 24-30″ bloom with poofy fall seed heads

Liatris ligulistylis — 24-36″ thin spire of late summer blooms, uses a very small footprint

Symphyotrichum oblongifolium — 18-24″ mounding, shrub-like perennial with late autumn bloom, provides some formal shape

Now, there’s FAR more to consider about this plant selection and arrangement, considerations such as root structure, reproductive behavior and senescence — all topics I explore in far more detail in the online classes and the book Prairie Up. But all that we need to really consider for now — from an introductory standpoint — is that these plants fill niches, provide continuous bloom succession for human aesthetic concerns and adult pollinator needs, are host plants to lots of insects, have decent winter interest, and stay at a manageable height and spread. They are all matched to one another and the site (soil, light, drainage).

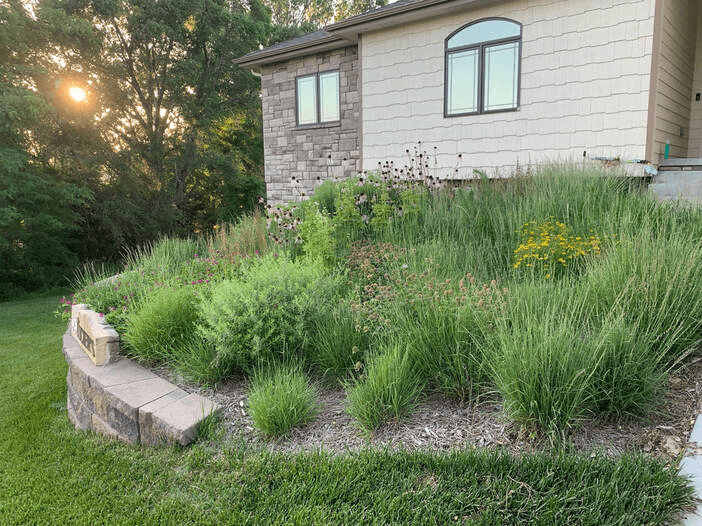

Here’s a wider view and different angle of the same bed. You can see a few gaps up front that need more grass additions, which is par for the course on any garden. Even natural gardens require gardening, it’s just that the management is more responsive to what’s going on any given week, requires less contact time per engagement, etc. Maintenance is on a calendar, and it often require intense and long periods of physical activity (mulching, weeding, etc).

I won’t go into too much detail on this site, as it’s principles are almost the same as the first example — and many of the same species were used, even though the species are starting to self organize themselves in a different way. And that’s great. The Bouteloua curtipendula matrix serves as a living green mulch from which clumps of Pycnanthemum tenuifoloum emerge, from which sporadic clumps of Echinacea pallida emerge, and among which Callirhoe involucrata creeps around and fills in gaps.

Annual maintenance for this and all spaces is a spring mow on the highest setting — about mid to late March every year. In the first year weeding is the biggest challenge, usually deadheading annual species like foxtail, crabgrass, horsetail, and ragweed (pulling brings more weed seeds to the surface). Sometimes in year 2 or 3 we’ll need to touch up with additional plugs. No big deal.

Here’s a mid range shot of two beds — the first is in the foreground. But I’m using this angle on purpose to show how natural wildscaping can blend well with more traditional strategies of garden design without losing any habitat value. It’s all about making solid plant choices — and even, over time, editing out choices that turn out to be incorrect. Sometimes you have to kill your darlings for the good of the whole.

These two front yard beds are split by a 6′ wide lawn path. That’s one cue to care. But as you can see in that far bed, some of the plants are presenting a more formal shape. Nearest the lawn path is a Baptisia minor, which tends to look like this for me in full sun situations. Behind it are two Smyphyotrichum oblongifolium specimens (one popped up on its own — works for me as it creates a nice triptych).

As for the rest? See how the taller Eryngium yuccifolium and Echinacea puprurea are in the middle of the bed. And the same for taller and yet-to-bloom Oligoneuron rigidum. There’s a matrix or what’s become a border of Bouteloua curtipendula and Schizachyrium scoparium. Then in back further still are some Cornus sericea which I coppice almost every year to keep at a lower 4 feet tall or so (coppice means cut down almost all the way to the ground — which I do in February or March most years). So there are traditional tiers, and none of the plants is super aggressive by seed or root runners — certainly not so in dry clay soil with good plant competition (aka plant density and layers, aka thick plant communities, aka, plants need stress to thrive).

So I know that was a lot to take in over a relatively quick post, but that’s honestly why I wrote a book and created online garden classes — so anyone could dive in deeper over and over as their gardens evolved. I think the ultimate lesson is this — try your best to research plants. And while from a design and ecosystem perspective there can certainly be a lot of variables to consider, start by focusing on plants with more compact habitat and slower reproductive methods. Once you get that base working in your garden, you can expand, experiment, and challenge yourself and neighbors more through different plant species.

In summary: avoid the weedy look by selecting plant species with shorter heights and less ability to self sow or run a lot. And make sure you mass flower species and repeat those masses. Think 3-5 plants in a clump, with those clumps repeated evenly 3-5 times in a small urban front yard.

I don’t know who that Michael Green financial analyst guy is who looked at one county in NJ to state

Oh that’s a cool plant, stiff goldenrod, Oligoneuron rigidum. I wonder if that would work in my garden. Maybe it’s